THE DRIVE OUT TO THE END of Fruitville Road is characterized by a gradual change in scenery. Churches of varied denominations cluster on both sides of the road—Faith Baptist, New Life Lutheran, Palabra de Fe—and these give way to empty lots adorned with centuries-old live oaks draped in Spanish moss. At a three-way stop 12 miles east of I-75, the topography is devoid of recognizable landmarks of the built environment—fast food chains, gas stations, traffic lights—with only the asphalt to serve as a constant reminder that humans have cut a tame path through the saw palmetto and wiregrass prairies of the state’s interior. Further still, the quality of the road changes abruptly, as if civilization decided these parts are too far to be worth the trouble of heavy machinery. Like the pockmarked asphalt, the landscape is now dotted with sloughs and oak hammocks, innumerable creeks and springs, populated by white-tailed deer. Even amidst an arid winter, the terrain bursts with life in all shades of green, which bodes especially well for animals both wild and domesticated. This idyllic landscape is also the paradise for a certain bipedal animal—real-life cowboys.

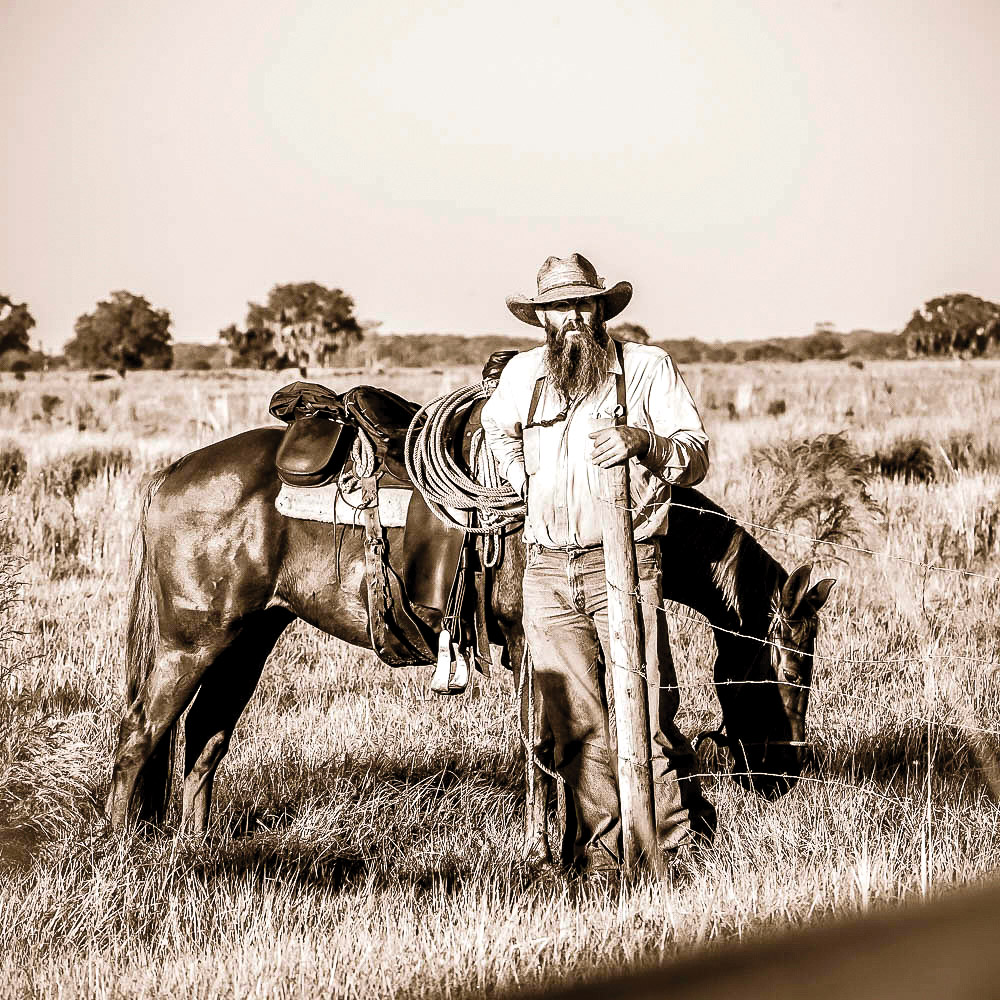

Jim Strickland is one such cowboy. His family has been in Florida’s centuries-old cow-calf game since the 1800s, and Strickland took over his family’s livelihood at the tender age of 17. “I wanted to be a cowboy at eight years old,” he says from beneath a cattleman’s cowboy hat in a hardy baritone with a slight Southern drawl. Today, he manages Blackbeard’s Ranch, a 4,500-acre property that has likely felt the heavy hooves of cows and calves for more than 300 years. The ranch shares a border with the northern wilds of Myakka River State Park, forming a nearly continuous tract of land. After a stint as a real estate agent and a stretch as a property appraiser for Manatee County, Strickland had a front-row seat to the sale and development of lands like those found on the ranch or in the state park, so he came back to ranching with a new perspective.

PHOTO BY MAX KELLY.

Nowadays, Strickland does more than make a romanticized living chasing cattle around: He’s added land steward to his résumé. “We’re right at the headwaters of the Myakka River,” he says, which means that Blackbeard’s plays a vital role in the hydrological health of the region. Both the pastures and pristine parts of the ranch help to filter impurities out of rain runoff, runoff that eventually makes its way into Charlotte Harbor and into the region’s drinking water. As Strickland tells it, the Florida lands he grew up on exist under constant threat of being paved over. When that happens, it’s typically without sufficient strategies in place to help mitigate the unseemlier effects of fertilizer runoff commonly associated with golf courses and water-hungry lawns. So, Strickland has taken up arms to help battle the encroachment of concrete and preserve the green spaces so vital to Florida’s ecosystem, and as he set out to assemble his squad of horse-mounted sustainability soldiers, he found what many would consider an unlikely ally.

PHOTO BY MAX KELLY.

Julie Morris cuts a formidable figure. She is tall, with piercing blue eyes, well-sunned skin and a quick trigger for talking all things conservation. She graduated from Rollins College with a degree in environmental studies, then earned a graduate degree in wildlife ecology and conservation from the University of Florida. A lot of her career has been spent advocating for conservation easements, in which landowners sell their land to the state or federal government at a discount in exchange for a guarantee that the land will be effectively preserved forever.

PHOTO BY MAX KELLY.

This is where the priorities of a cowboy and a conservationist overlap. “People have a misconception about agriculture and ranches,” says Morris, “but ranchlands are the next best thing to pristine—they protect a lot of habitat.” Lands like the native sloughs or orderly pastures on Blackbeard’s Ranch do more than feed and water well-adapted cows with nutrient-rich grasses: They attract birds and creepy-crawlies, provide a pollination amusement park for bees, and create a wildlife corridor in which endangered species like the Florida panther can thrive. So, the domesticated cows and calves raised on Blackbeard’s Ranch have unwittingly become an important cog in the living machine that is Florida’s ecology.

PHOTO BY MAX KELLY.

Strickland and Morris’s collaboration often sees them side-by-side on a Kawasaki Mule, the cowboy keeping his eyes peeled for the condition and location of his herd, the conservationist adding to her to-do list of environmental projects that will support the native landscape best—a controlled burn here, a clearing of overgrown underbrush there, perhaps the addition of a drainage ditch to prevent excessive flooding. Strickland obliges Morris in her counsel, no matter the scale, because he is committed to running one of the most sustainable cow-calf operations in the state. “Of all the ranches in the state of Florida, our way of doing it accounts for only two percent,” he says, and in a billion-dollar state industry, he is willfully cutting himself out of a lot of money. “Rancher’s don’t get rich selling beef anyway,” he adds, “They get rich when they sell their land to developers.” In addition to adopting science-based sustainability practices for the land, Strickland has also imposed a set of exacting standards on the production of his bovine commodity, not to win blue ribbons in the court of public opinion, but because he believes it is the right thing to do. The standards include, among other things, a commitment to producing the cleanest grass-fed beef possible. No antibiotics or steroids course through the veins of his free-range herd, just pure protein and nutrients from clean fields of green.

This yields top-shelf meat—tender, flavorful, red and juicy. Strickland can finish the beef with grass or grain, the latter yielding a higher fat content while the former is considered a more premium product. After a long day in the sun, Strickland likes to cut into some of the beef he ages on the ranch and light up a gas grill for a simple rancher’s lunch. It might include anywhere between three and ten ribeyes depending on the number of cowboys and cowgirls (or formerly vegetarian conservationists), along with a buttered baguette wrapped in foil and tossed on the grill’s top rack. “I’m not much of a cook,” he says, though with meat so lovingly raised on his open pastures, it would be hard to go wrong with just a dash of salt and pepper before throwing the cuts on the grill.

“We have the only prime beef that’s born, raised and processed entirely in-state,” says Strickland. He and Morris hope to leverage that seemingly inane fact into more awareness for the conservation of unspoiled land as well as ranchlands. Great chefs and experienced foodies all say the same thing: Good food is as much about the story as it is about the preparation. An apple can be an apple, or it can be the symbol of a family orchard maintained for several generations by descendants of the original planters. In the latter, the apple might not actually contain more sweetness or a ruddier glow than an apple from a neighboring orchard, but when it’s prefaced by a story, it speaks to the human propensity for a good tale. For Blackbeard’s Ranch, it’s no different.

In their effort to bring more awareness to their advocacy for conservation, Morris and Strickland conceived of a plan both simple and brilliant. “We started using the food to tell a story,” says Strickland. They now give tours to legislators, conservationists, ranchers, chefs and, lucky for this author, media outlets, and these tours most often end with a version of the preceding rancher’s lunch. In these cases, the steaks serve as a pristine selling tool for a worthy cause. Blackbeard’s has also set out to select a handful of restaurants to carry its meat products, with Beach Bistro on Anna Maria Island as the earliest adopter. “We’ll probably cap it at just three or four restaurants,” says Strickland, “because producing beef this way means you can’t produce the volume of more profit-driven beef suppliers.”

But, again, the steaks are just a means to an end, a way to package sustainability and environmental stewardship in a palatable format. A porterhouse can just be a cut of beef, or it can contain within its fibers the whisper of a story about a rancher and a conservationist vanquishing the evils of land mismanagement. That sounds like a darn good steak.